This day’s hearing addressed the murder of Habil Kılıç. At first, murder investigator Wilfling from Munich reported, devoid of self-criticism, how meticulously the murder case of Habil Kılıç had been investigated – almost exclusively in connection with organized crime. Habil Kılıç’s widow and mother-in-law testified in the afternoon and were thus the first relatives of a victim to speak out in court. Their statements indicated the suffering and the extent of injustice they had been subjected to.

The day’s hearing began at 9.47 a.m. Carsten S.’s defending attorney Pausch was represented by attorney Potzler.

The first witness to be called was the retired murder investigator Josef Wilfling, an investigator also known from the media, who had lead the investigations into the murder of Habil Kılıç in Munich on August 29, 2001. He reported that his homicide squad had been alerted just after 11 a.m. that there had been a case of homicide involving firearms at a grocery store in Bad-Schachener-Straße. The shop’s owner had lain in a pool of blood behind the counter. First measures had then been taken.

It had been possible to determine the time of the crime pretty closely due to phone calls and witness statements. A customer had been in the shop at 10.30 a.m., and at 10.31 a.m. Kılıç had called a colleague; the phone call had lasted three minutes. The murder had to have occurred after this. At 10.40 a.m. another customer had entered the shop and had found Kılıç. A postman had called the police at 10.52 a.m. from a landline. In a questioning of residents, two neighbours from the other side of the road had independently from one another stated to have seen a dark Mercedes in front of the shop, into which a dark-skinned man had gotten having just left the shop. The vehicle had then driven off with squealing tires. Later it had been found out that these statements had been “a fake”. One of the witnesses had had an alcohol problem, had come up with the alleged observation and told the other witness about it. There had also been a reference to a vehicle behind the store, a silver Ford Escort with open doors, next to which a Turkish man had stood. It turned out later that the vehicle belonged to a pensioner. The observation had had no relevance to the crime. Moreover, there had been statements from two residents. One of them had said that she had seen two young men in dark clothing and with bikes, once at 9.30 a.m. and then again a bit later. The second witness had stated to have seen two young men at about 10.45 a.m. from her balcony who had gotten onto their bikes and cycled away. The observations of both witnesses had been nearly identical; there had not been a closer description of the two cyclists. According to the statements the two men had been athletic; the description of their age had ranged from 18 to 30. They had looked like bike couriers. The vehicles had then been searched for. The cyclists had been looked for as witnesses, there had been no indication that they could have been the perpetrators.

Wilfling reported that a coroner had been consulted at the scene of crime, who had determined that Kılıç had been killed with two shots to the head. During the first shot Kılıç had been standing. The second shot had hit Kılıç at the back of the head as he was falling. Wilfling stated that this had been an “absolutely professional” execution. He said the second shot had been “like a finishing shot”. One of the bullets with the calibre 7.65 had been found outside; it had probably been carried there unintentionally by the first responders or witnesses. The other one had later been found in a wall by the counter. No bullet casings had been found, but a piece of a plastic bag. Therefore it had been assumed that the weapon had been in a plastic bag when the shots were fired. There had been no other pieces of evidence, nor traces of the perpetrators. A murder with robbery had been excluded, as both the cash register and Kılıç’s wallet had been left untouched.

Afterwards, Wilfling went through a folder of images connected to Kılıç’s murder case. First a city map and several aerial views were shown. They illustrated that the scene of crime was situated in a corner house. Wilfling reported that there was a police station a hundred meters away. Right next to the house there was a passage leading to some blocks of flats. The two witnesses who had seen the cyclists had lived in these houses. Pictures were shown from the shop’s exterior and then the interior. Wilfling reported that the perpetrator could only have come through the shop’s front door. In summer, this had always stood open, which was why no further evidence had been found there. Then images of Habil Kılıç’s bloody body were shown. Some tubes leading to the victim’s mouth were still visible, originating from an attempted reanimation. Many images from the shop’s interior were shown. Wilfling reported several times that the place had been searched meticulously, every square centimetre had been examined. There had been countless fingerprints, which had however not led to anything. There also were some images from the family’s flat close-by, which had however been completely inconspicuous.

After a break, the co-plaintiff attorneys began the questioning of the witness. Attorney Scharmer asked about a note according to which the bullets had been sent to the LKA with the addendum “very urgent”. Wilfling reported that they had known of a series of systematic murders and had wanted to know whether this case was one of them. Concerning other indications that this crime was one of a series, Wilfling pointed out: “First and foremost the victims.” All of them had been Turkish citizens; it hadn’t taken long to recognize the pattern. There had been other crimes in 2001 involving weapons with the calibre 6.35 and 7.65, which had been connected to drug cases. And there had also been vague indications of a narcotics background in the Ceska murder-series. It had transpired later that this had not been relevant to the crimes. Scharmer wanted to know whether other motives had been examined. Wilfling replied that they had investigated into any imaginable direction. Kılıç’s relatives had never been suspected. Kılıç had mainly moved within the Turkish community, therefore it was obvious that they had investigated in that area. That there had also been witness reports in Nuremberg that had referred to cyclists had surely been discussed, but only at a later point. He himself had not been a member of the “SOKO Halbmond” (the “special commission crescent”, referring to the Turkish flag). There had been no indication of a connection between the crimes in Munich. Wilfling: “Today we know better, today I also know that these were the perpetrators.” Attorney Narin confronted Wilfling with a statement that the person who had allegedly run from the shop and gotten into the Mercedes had been a “mulatto”. Götzl complained that this was not correct. Wilfling said he believed Narin would have come to the same conclusions, if two witnesses had independently made the same observation. It was “completely normal that this was the primary lead”. The cyclists had been described as couriers. It taken a while until they had discovered that the testimonies made by the two witnesses from across the road been wrong. Narin confronted Wilfling with the report that a witness had said he reckoned a suspect had been a Turk and had had a slim moustache, a so-called “Mongols beard”. Wilfling pointed out that this statement had been made by a pensioner. A facial composite had been created, yet had led to no results. Moreover the man had been looked for as a witness, not as a suspect. After a question from attorney Rabe, Narin asked Wilfling about his statement made in front of the NSU enquiry board in Bavaria. Wilfling stated that a delegate of the Greens had repeatedly asked why they hadn’t known that the cyclists had been neo-Nazis: “Unfortunately, I then replied: ‘Have you ever seen a neo-Nazi on a bike?’” Attorney Daimagüler asked whether the fact that the two possible witnesses, the cyclists, had never come forward, had changed anything about the assessment that they were witnesses. Wilfling stated he hadn’t thought it possible at the time that the cyclists could have been the perpetrators. One had to put oneself in the position of the time, today one knew better. They had seen the cyclists as witnesses; it hadn’t been possible at the time to say who might be a suspect. Daimagüler wanted to know whether a political background had also been considered. Wilfling said this had been checked. Four fifths of the witnesses had been Turkish, there had also been clues leading to the PKK and the Grey Wolves. A witness had said it could have been a “hater of Turks”, but had meant the PKK. One also had to consider the mode of the crime; it had been a systematic execution with a conspirative approach. They had investigated several right-wing homicides. These had all been brutal, loud attacks; the perpetrators had made no attempts to conceal this. However, there had been many indications leading to organized crime. Wilfling: “And don’t pretend as if there is no such thing as a Turkish drug mafia.” There had also been clues leading to the Netherlands. Daimagüler asked whether there had also been clues leading to the Netherlands in the case of Kılıç, as this was being addressed here. Wilfling replied that this had not been the case with Kılıç, but in Nuremberg. Wilfling: “Mr Kılıç was a law-abiding, hard-working and humorous human being.” Attorney Rabe asked which victim in Nuremberg had shown connections to the Netherlands. Wilfling replied that, as far as he knew, this had been Özüdoğru. Federal Prosecutor Diemer complained loudly, asking what this was supposed to yield. The Prosecution assumed that Böhnhardt and Mundlos were the perpetrators and Zschäpe was being accused to have been an accomplice. Questions were supposed to address these crimes. Rabe pointed that the Prosecution was dealing with the question of the background to the selection of victims. Diemer replied the Prosecution assumed that the victims had been chosen as they were foreigners; questions were to address the charges. In turn, Rabe replied: “If a police officer suggests here that the victims were criminally involved, then the Accessory Prosecution will have something to say to this.” Attorney Kuhn asked whether any other conclusions had been drawn, apart from the exclusion of murder with robbery. Wilfling replied everything had been investigated. The victim had worked in the central market hall, a known transfer site for drugs; he had had debts and they had investigated whether the murder could have been a contract killing. As the debts had been discussed, had it been considered that it would have been likely for the perpetrators to take the money, asked Kuhn. Wilfling replied that he did not know. Attorney Erdal wanted to know whether Wilfling knew of the arson attacks in Mölln and Solingen. A heated argument between Presiding Judge Götzl and Attorney Erdal ensued. Götzl stated that Erdal should ask questions to the issues at hand. Wilfling said: “Now let me tell you something: We all want to solve these cases. We aren’t blind in the right eye.” Erdal wanted to know why they hadn’t investigated the right-wing scene. Götzl cautioned Erdal. Erdal raised his voice and said the witness was operating with half-truths, there was only one clue referring to the Netherlands. An agitated Götzl claimed that Erdal was too emotional. They would take a break so he could calm down.

During the break, the defendant André E. and Wohlleben’s defending attorney Schneiders had an animated conversation.

After the break, attorney Mathey asked whether the Kılıç family had been taken care of. Wilfling reported that a connection with the “White Ring” had been arranged, there had been intensive contact. After questions posed by Zschäpe’s defending attorney Sturm, attorney Schneiders asked about the questioning of a Mr D. Wilfling reported that D. was known to the authorities as someone who always claimed to know something about everything. His statements, also those referring to Kılıç, had to be treated with caution. There had been a well-known saying among police officers: “If you have Mr D. as a friend, you have no need for enemies.” Schneiders pointed out that D. had referred to rumours on the central market about a delivery of heroin, which Kılıç was allegedly connected to. Wilfling repeated that the witness D. had to be treated with caution. The leads had been pursued, without any result: “When a lead is false, there can be no result.” Wohlleben’s defending attorney Klemke asked about the ‘Milli Görüş’. Wilfling replied that it was possible that this had been mentioned in one of the fifty hearings of witnesses. However none of these references had led to anything.

Co-plaintiff attorney Kanyuka then asked if anything had been peculiar about the cyclists. Wilfling stated that one or both of them had worn a headset. If only one of them had worn a headset, this may indicate that there had been a third person. However, this had not been resolved.

Then two statements in accordance with § 257 of the code of criminal procedure were brought forward. The first was read out by attorney Lucas, representing the Accessory Prosecution Şimşek. It addressed attorney Rabe’s questioning of the witness. As part of the main trial it had to be clarified which background there had been to the selection of victims. This was not about a new investigative commission. Yet the verdict had to clarify why the victims had been murdered. Thus every lead had to be pursued. The trial also had to protect post-mortal personal rights; rehabilitation was of the utmost importance. The Şimşek family had been confronted with massive accusations. He was calling upon the representatives of the Federal Prosecution not to reopen this discussion every time. The aim was also to achieve understanding. Then attorney Scharmer read out his statement. He stated that questions concerning the investigations were also relevant to the question of guilt, regarding the issue that the crimes could have been prevented.

A lunch break was then announced from 12.15 to 1.35 p.m.

Following the lunch break, Federal Prosecutor Diemer read out a statement in response to those of the Accessory Prosecution. He pointed out that legally speaking, these statements had not complied with § 257 of the code of criminal procedure; that his own statement was also formally not correct, but that he had to answer, as the Federal Prosecution’s interventions had been objected to. He remarked that questions that would delay the trial had to be objected to. Missing or prior leads of investigation, such as a right-wing background, were not relevant to the defendants. Whether possible crimes could have been prevented and if so, how, had to be clarified elsewhere; due to the procedural principles and the requirement of swiftness these questions could not be answered within the trial. Co-plaintiff attorney Lucas replied that the question whether earlier leads of investigation were still being adhered to had to be permitted and was part of the main trial.

The next witness to be called was (first detective chief superintendent) Manfred H. As detective of the K11 in Munich he had carried out a presentation of images to the witness S. on behalf of the BAO Trio (a special unit concerned with the NSU murders) in 2012. She had seen the afore-mentioned cyclists in the Kılıç murder case and was asked whether she would recognize them. She had told H. that she thought she could see resemblances, but couldn’t say so with certainty, as she had only seen the cyclists from above. However, she repeated her earlier statements, according to which the cyclists had been young men, both wearing dark clothes, and one of them taller than the other. The taller of the two had had a rucksack on his back. After Böhnhardt and Mundlos had been shown in the media, she believed to have recognized the smaller of the two in the media.

Then the next witness was called, detective chief superintendent Bruno A., who also worked with the K11 in Munich. He was also asked about a presentation of images on behalf of the BAO Trio, which he had carried out with the witness M. who had also seen the cyclists on the day of Kılıç’s murder. He reported that he had visited the witness at her home in 2012. M. had shown him there where the two cyclists on silver bikes had departed. She had spoken of two young men in dark cycling gear, yet hadn’t recognized anybody from the images. She had called after the cyclists that they weren’t allowed to cycle on the green belt, yet they hadn’t reacted to this.

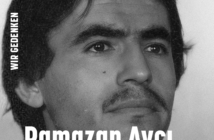

After another break, relatives of one of the victims were called for the first time. The first witness was Habil Kılıç’s widow, P. Kılıç. The 51-year-old former retail saleswoman entered the courtroom and sat down at the witness table. Her attorney Manthey initially remained seated at the back of the courtroom. Götzl instructed the witness on her obligation to be truthful and asked for her address. She answered only very hesitantly and did not want to give the name of the place in the courtroom. After a short discussion she handed Götzl her identity card. In the direction of Zschäpe she said: “What this woman has done…” Götzl asked what kind of a person Mr Kılıç had been. P. Kılıç reported that he had been very good to her, had been a father of a family and a decent man. She had met him on vacation in Turkey, which had been very nice. Götzl asked for details, yet P. Kılıç asked him in return whether he hadn’t read it all, and said that he should ask her attorney; it was more important that this woman (Zschäpe) was prosecuted. Götzl tried to explain why these questions were being asked, that she had been called to speak about her deceased husband. Bit by bit she reported that Habil Kılıç had worked as a forklift driver at the central market, had gone there every morning at 3.30 a.m. and had returned at lunch time, after which he had helped her in the shop. Götzl read from a note from an earlier hearing, citing that the shop had been opened about a year before the murder, in March 2000. On Saturdays Habil Kılıç had tended to the shop on his own, so that she could sleep longer. At the time of the murder the witness had been on vacation in Turkey. When Götzl asked what the situation had been like after the killing of her husband, she replied: “How can it be? Can’t you imagine it, first losing your husband and then the shop? The way people talk about it, when you are treated as a suspect. You can read it with Mr Manthey, what should I say in front of that woman (Zschäpe)?” Götzl said that when he asked a friendly question, he also expected a friendly answer, this wasn’t about that woman. P. Kılıç went on: „They” had caused a great amount of damage, first murdering her husband, then ruining their circle of friends, the whole financial aspect, “they destroyed everything, everything.” They hadn’t been able to stay in the flat, the walls had been smeared, the furniture full of black marks [from the search for fingerprints]. They had had to give up the flat, as well as the shop, which had still been full of blood when she had received the keys back from the police. “I then said I couldn’t give up everything. I have German citizenship, I have to carry on, find a new job. I said I had to clench my teeth and not lose hope.” The police had also investigated her family and her friends, also those in Turkey. A lot of time had been lost due to these investigations.

She had had to give up her shop for health reasons and was still in medical treatment. Götzl wanted to know whether she had had mental problems, yet P. Kılıç did not want to answer this and referred to her attorney and her doctors, everything had been noted down. Her attorney then also came to the front and sat down beside the witness. Götzl asked about her financial situation. The witness reported that her parents had had to support her. Nowadays she received a pension of 177€, and now after several years another pension from her medical insurance. Asked about the whole situation she said: “It’s not easy, you have to be strong, but you can’t be that strong, at some point you break down.” She reported how she had gone to the scene of crime and had seen a man on the other side of the road, who told her that he had been strangled by Nazis, but when she had called the police, he had already disappeared. Asked whether the attack could have been aimed at her, as it had been her shop, Kılıç replied that she didn’t know “that woman” [Zschäpe] and had had no problems. Götzl wanted to know more about her husband. She reported that he had enjoyed driving and had often gone swimming. Götzl referred to an earlier statement saying that the couple had married in Turkey in 1985. Due to laws applying to foreigners Habil had not been able to come to Germany until three years later. Co-plaintiff attorney Kanyuka wanted to know how her then ten-year-old daughter had reacted to her father’s death. P. Kılıç said she had tried to distract her, and had tried to make sure that it wasn’t talked about at home. She said that if she had killed somebody, she would have been released after ten year, but this way “I feel as if, for the past 13 years, I have been strung up with a chain around my neck… for life!”

After a break of about ten minutes, a translator initially translated for P. Kılıç, but after the first few questions she began to answer in German once again. Attorney Kanyuka once again asked about her daughter’s school. Kılıç replied that she had had to switch schools; moreover, they had had to move, as they had not been able to continue living in that flat. No questions were asked by the defending attorneys.

At 3.45 p.m., the last witness of the day was called, P. Kılıç’s mother, mother-in-law of the murdered Habil Kılıç. The 74-year old certified chemist Ertan O. answered Götzl’s question as to how the victim had lived. Just the day before his death they had shared a cup of coffee, he had been healthy and everything had been alright. The next day one of her daughter’s neighbours had called and said that something wasn’t right. She had thought that her son-in-law might have broken his foot, but the neighbour had only told her to come to the Bayernstraße 34. There she had been questioned by the police officer V. for three hours, who, amongst other things, had wanted to know how she had gotten along with her son-in-law. At the time she had not been told of her son-in-law’s death. After three and a half hours the phone had rung, and after the call, the policewoman V. had turned around and told her that her son-in-law had died and was in autopsy, but that the organs were undamaged. Even when Götzl repeatedly asked about this description of events, she abode to her account that she had only been told of his death after three hours. Ertan O. reported: “If they had told me, I could have maybe held his hand in his lasts moments.” When a note from the officer V.’s report was read out, stating that she had been told of his death prior to the questioning through the police, she simply said “rubbish”.

Habil Kılıç’s mother-in-law was then asked how the family had coped with his death. She also reported that her daughter had initially not been allowed to live in her flat, and that later everything had been covered with black powder from the taking of fingerprints. Nonetheless they had had to pay rent for both the flat and the shop. They had also been attacked by the media. These had reported on drugs and affairs with women, “it was a complete catastrophe; it was no longer a life”. Götzl asked about her granddaughter. Ertan O. reported that the school had initially wanted to kick her out; the headmaster had said she was afraid about the other children. Only with great difficulty had they achieved that the granddaughter could stay at the school. The medical treatment was also addressed again. Götzl asked for details. The witness only stated that she had been in continuing medical treatment. At the end of the hearing Götzl returned to the hearing carried out by the policewoman V., yet Ertan O. insisted that it had happened as she had reported. After the questioning she had driven to the shop, where everything had been roped off with barrier tapes; policemen in white suits had been present. The body had no longer been at the scene of crime. Regarding the crime’s consequences she went on to say: “Why were we the only ones to be investigated, for 13, 14 years? Why weren’t the perpetrators looked for, this was time wasted. Do you know how often I had to provide fingerprints?”

The day’s hearing ended without further questions or statements from other participants of the trial at 4.20 p.m.

Co-plaintiff attorney Scharmer made the following statement regarding the questioning of leading investigator Wifling:

“When you consider the witness’s views, it doesn’t surprise you that for over ten years, the investigating authorities were looking into the wrong direction. Instead of checking whether there was a connection between the suspects in cycling gear in Nuremberg and the cyclists seen at the crime scene of Kılıç’s murder, the authorities carried out a “meticulous” search for “drugs”, “the Mafia” and “the PKK”. It is revealing that the witness, a retired, highly ranked detective, stated that he couldn’t imagine that two cyclists, dressed as couriers, could have been suspects, but in his reports instead referred to suspected “Mulattos” or a “Turk with a Mongol’s beard.”